- Home

- Andrea Randall

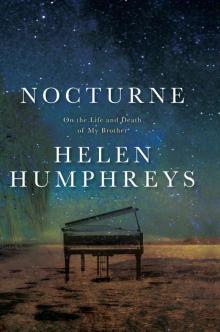

Nocturne Page 6

Nocturne Read online

Page 6

Annoying thoughts. Inappropriate thoughts, considering she was a student. A student who was out on a date with her boyfriend.

The band slowed down, and the couples on the floor moved closer together. Karin folded herself into my arms, nestling her chin against my shoulder. She was pressed fully against me, and we swayed slowly with the music.

“Gregory … ” Her whisper was right in my ear. I squeezed my arms tighter around her, because that seemed all the response necessary.

I sighed a little as Savannah and Nathan swung into view again. They were appallingly close, and his hand was resting just on the top of the curve of her ass. She was truly a remarkable young woman. And probably deserved someone a lot better than Nathan, who was little more than an overgrown boy. I almost let my mind run to the thought of her in bed, and my body involuntarily responded.

I tried not to freeze, because Karin noticed. And pressed herself against me, tighter. “Gregory?” she said.

“Yes, Karin,” I murmured.

“Let’s go back to my place?”

Gregory

I checked my watch. 4 p.m. I was late. I hated tardiness. It showed a lack of respect. But today it was unavoidable. I’d spent the last three hours grading papers for music theory class, which I shouldn’t have been teaching in the first place. Once I started something, it was difficult to quit. And it was my luck that at 3:30 I’d pulled the next paper off the stack.

Savannah Marshall.

I want to be clear. I’m a fair instructor. Some students think I’m too harsh, too demanding. But this isn’t a liberal arts community college for those who desire to enter the fascinating world of cosmetology or small business finance. This is the premier conservatory in the world, where we train musicians who will go on to the top of their fields. I would do my students no favors by coddling them and giving them false illusions, which would only be shattered by harsh reality when they left the confines of these walls.

That said, her paper presented a dilemma. On the one hand, it displayed a level of brilliance and sheer power that was rare in students her age. On the other hand, it was a muddle of ridiculous assertions. Instead of technique, she wrote about feelings. Instead of placing the music in its proper context as a work of sublime art, she wrote about its historical context and how it represented the people and relationships involved in its composition.

In short, she understood nothing I’d been teaching. Or worse, she understood it, and dismissed it.

At 4:01 p.m. I scrawled an F across the top half of the cover page. I knew as I wrote it that it was harsh. Heavy-handed, even. But, half-steps are best left to scales, and have no business in my classroom. She needed to be taught a lesson. Sighing, I stood, and hurried out of the office.

Thanks to Savannah Marshall’s bizarre and irrelevant paper I was nearly four minutes late arriving at the practice rooms.

In the hall, I found a depressingly middle-classed young couple. At a glance, I could tell he was a computer something or other for some company on 128, and she was probably an elementary school teacher. Perhaps a music teacher, which I hoped to God not, because she would soon be attempting to tell me how to do my job. Between them stood a young boy, perhaps twelve years old, with what appeared to be an undersized cello case. It was beat up and marked with a rental agency’s logo.

“Good afternoon, I’m Gregory Fitzgerald,” I said.

The mother stepped forward. “Susan Donovan,” she said. “This is my husband David, and our son, Robert.”

Robert looked nothing like the couple. She prodded him forward. I felt unsure. Did one speak to a child that age as if they were simply a short adult? Or give orders? My father once told me that I’d never been twelve. Of course, as much as I loved my father, it became clear early on that he had no idea what to make of me.

Short adult then. I reached out a hand, not to the boy’s mother or father, but to him. He couldn’t see the hand of course, so I reached down and took his, gave him a not too firm handshake. I don’t generally shake hands, because men like to engage in stupid games of who can grip harder. My hands were my music. They were my life.

The father spoke. “We’d like to thank you for meeting with us ...”

I cocked my head. “I was under the impression your son was the student, not you?”

David Donovan looked somewhat shocked, and opened his mouth to speak, but his wife was the faster of the two, because she quickly said, “We thought we’d spend a few minutes explaining Robert’s issues—”

“Unnecessary. Robert ... come. The practice room is right over here.”

I put a hand on his shoulder to guide him.

“He doesn’t like to be touched ...” his mother said.

I waved her off, and the kid came willingly enough.

“Have a seat,” I said to him, setting my practice cello in its case against the wall. This was a relatively inexpensive instrument that I kept at the conservatory. The Montagnana was only played for rehearsals and live shows for the symphony.

He put a hand out, and said, “Where’s the chair?”

I was already unsnapping the case for my cello, but I turned and took his hand, then stretched it out so he was touching the back of the chair. Then I turned away.

Gently, I lifted my cello from its case, then took a seat. A moment later he’d found his own seat, and took his out. In the meantime, his irritating parents were pushing at each other, because only one of their heads at a time would fit in the small glass window in the door.

I studied him as he fumbled with his case. He had extensive scarring around his eyes. I couldn’t tell if he’d been in a fire, or what, but he wasn’t born blind. Something had happened to him. Whatever. It wasn’t his eye that mattered. It was his hands, and his ears.

He was awkward with his instrument, a training instrument intended for smaller children. It was in terrible condition, obviously rented. The bow was caked with rosin, the screws and fittings oxidized, and the hair brittle and glazed. The cello itself had multiple scratches. It would take a magician to get a decent sound out of that instrument. I almost felt a fit of rage over the mistreatment of the instrument, as well as whatever shyster had rented it to the boy’s parents. It was typical that a beginning musician would be given an instrument that would be most difficult to play.

“Why do you want to learn cello?” I asked.

Robert just looked confused by the question.

“You’re blind, not mute, correct?”

At that, he recoiled a little. “I can talk.”

“Then tell me why you’re here.”

“My mom ... she … um ...”

“Your mother wanted you to learn? Does she think because you are blind you’ll be some sort of prodigy?”

He flinched, then nodded, just a little.

“And what do you want?”

His face turned away from me, his blank, scarred eyes moving around aimlessly. Then he said, “I want to stop feeling like I’m a freak.”

I bit the inside of my cheek. All right, then.

“Then listen.” I set the bow to my strings and began to play. The same beginner piece I’d played for my useless music theory class a few weeks before. Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major. The first music I’d learned on the cello. The music that had transformed my life.

As the notes rang out in that tiny practice room, I watched the boy. I watched his expression. I wanted to see inside his head. See his thoughts. See if he felt it. If he believed it.

And then something quite magical happened. He began to sway in his seat. He did feel it.

Finished, I said, “For you to learn to play like this, you’ll practice until your fingertips feel like they’ll split open. Day and night. You won’t stop when you’re hungry. You won’t stop when you’re tired. You have to want it enough to give up your entire life for the music. You have to be able to coax beauty out of nothing. Do you understand me?”

He nodded his head. Quickly. I thought about the diff

iculties of teaching this boy. I wasn’t the instructor to get him started. But I would ensure he found someone.

I leaned forward until our faces were almost touching. “If you’re willing to go that far, then I’ll find someone to teach you.”

I stood and put my instrument away in its case. Then I opened the door, and walked past his parents, who had to scatter in front of the swinging door. I paused for just a moment and turned back toward them. “You’ll need to get him a decent instrument. That one isn’t going to work if he’s going to seriously learn. Call me on Thursday and I’ll find you an instructor.”

Without another word, I walked back up the hall to the stairs, back to my office.

Savannah

I squinted again and took my pen out of my mouth. The top of it was thoroughly chewed. Bad habit, I knew, but sometimes when I was really concentrating I tended to chew on whatever was at hand.

I’d been sitting in the coffee shop for two hours, working on a composition. This wasn’t an assignment, though it had been inspired by one. Just before spring break, I’d completed a paper in music theory on Claude Debussy’s music and life. That led to some speculation on variations that might be possible with the Debussy’s Claire de Lune. So I’d taken the original composition and begun to rework the beginning, which was all piano, into a cello and flute duet. For hours I’d worked on it, closing my eyes. Imagining the layers of notes, the point and counterpoint.

But now I was stuck. My legs were cramped, my tea was cold, and I needed a break.

So I shook my head, took my earbuds out, and stood. I hadn’t actually been listening to music with the earbuds. But keeping them in served two purposes. First, it helped shut out some of the noise. Second, it deterred would-be conversationalists. I walked up to the counter and ordered another chai latte, then waited. And then it hit me.

I closed my eyes. And then I imagined ... the Claire de Lune, but transposed with Debussy’s Nocturnes. It would take a lot of adjustment in both pieces, but the end would be … a magnificent and beautiful contradiction. Haunting.

Someone tapped my arm, and my eyes jerked open. The barista stood there looking puzzled and tapping a foot in impatience. “Are you all right?” she asked.

“Yeah ...” I was a little breathless. “Thank you.”

I turned to hurry back to my seat and get to work, then came to a halt.

Gregory Fitzgerald sat at the counter diagonally opposite where I’d been sitting the last two hours.

He had a frown on his face as he paged through a stack of papers. Assignments, from the look of it. Sitting like that, his head bent over the papers, he looked younger than I usually thought of him. Less intimidating. More ... approachable, perhaps because his frown merely represented concentration rather than his usual scowl.

I found myself walking back toward my seat along a path that would take me by him. I came to a stop, pausing only long enough to take a breath and reconsider, before sliding into the seat next to him.

He continued to study the paper he was reading, his blue eyes scanning through the lines of text. He paused, circled something with a red pen, and then continued on, his concentration so intense he didn’t notice me staring at him, studying him.

I’d never been this close to him for more than a few seconds. This close, I could see that his right eyebrow rose slightly higher than the left, just by a fraction of a centimeter. He had a profound focus on his work, to the exclusion of everything else in the room. If I set fire to the place, would he even notice?

Then he reached out and touched his empty teacup and lifted it to his lips. His eyes shifted from the paper to the empty cup, breaking his concentration. He set the cup down, looked up and met my eyes, and I felt a sudden jagged thrill of fear.

“Hello.” My voice wasn’t exactly shaky, but I felt an edge to this entire encounter.

His eyes widened, and his lips curved up into the slightest smile. “Miss Marshall. A pleasant surprise.”

“Savannah,” I replied. “I’m on spring break.”

“Gregory, then.”

I shifted in my seat and licked my lips before speaking again. “Term papers?”

“This? No. I’m actually reviewing a list of instructors who might be willing to take on a disabled student. Blind.” He struggled with his words, which I found unsettling.

“Differently abled.” I chuckled.

“What?” He scrunched his eyebrows together, genuinely baffled by my statement.

I shook my head. “Never mind. How old is …”

“Oh, twelve. Him. He’s twelve.” Gregory sank down a little in his seat and rubbed the back of his neck.

“What instrument does he play?”

Gregory’s eyes shifted away from me and toward the window. “Cello.”

“Why aren’t you doing it? You teach.” I shrugged and rested my elbow on the table, facing him as I propped my cheek up on my hand.

Gregory took a deep breath and closed his eyes for a minute. When he opened them, he finally faced me. “I’m not … I just don’t think I’m qualified to handle such a task.”

“Certainly not, if you are referring to the student as a task. Seriously though,” I continued when it looked like he was going to cut in, “you could totally teach him. Marcia Taylor is my roommate and she says you’re a genius.”

He chuckled a little. “As much as I appreciate the observation—”

“I’m serious,” I cut in again, sitting straight in my chair. “I was nine when I grew tired of racing up and down the rows of chairs in an empty opera house during line rehearsals. I wanted to do something. I wanted to play something. The woodwind coordinator for the orchestra was a flute teacher, and my mother paid her to start teaching me. She resisted at first because she’d never taught a child.”

“I can relate.” Gregory nodded and crossed his arms in front of him, leaning back until he was resting against the window.

I did an unattractive half-laugh, half-moan at the memory. “She was awful. Seriously. She would teach me notes and would start out by doing the standard circle diagram of the flute keys, filling in the ones where my fingers needed to go. But, then,” I reached forward and took hold of Gregory’s hand, ignoring the shocked look on his face, “she’d take my fingers and manipulate them to solidify her point. I’d be holding the damn flute with her bossy hands all over me, as if it were appropriate for a nine-year-old to be playing an open-hole flute to begin with.”

Gregory’s eyebrows shot up. “You learned to play on an open-hole flute?”

I smiled a little at his reaction to my starting with a flute many don’t use until they’ve played for several years. “She may have had no finesse whatsoever in dealing with me, but she got the job done. I’ve never played anything but open-hole, and I have her to thank for drilling me and training my hand muscles to reach far enough to cover the keys. My point? You can teach this kid, if you want to.”

Gregory nodded slowly, looking at the table just past our hands.

Our hands.

I’d gotten so swept up in the story of Giada Barone that I’d left my hands on his … demonstrating a middle E-flat. Shifting slightly to try to pull my hands away without creating an awkward moment, my fingers slid in between his and from a distance it would have looked like we were holding hands.

All the sound in the room disappeared as I felt the fingers on his left hand tighten around mine. They were as strong as I’d imagined, but softer than I’d expected. His thumb skimmed over one of my knuckles, and I yanked my hand away. I shot my eyes to his face as my lips parted, my lungs begging me to take the breath they’d been waiting ten seconds to receive. Gregory’s eyes came back from his contemplative stare into nowhere as I cleared my throat and wrapped both hands around my latte mug.

“Oh, Savannah …” He sounded rather panicked as he dug for something to say.

It was just an accident. A reaction. He wasn’t thinking. This isn’t about you.

I smiled as wide as

I could in order to hide my surely flushed cheeks.

“You should give that kid a chance, Gregory. You could change his life.” I shrugged, speaking too quickly. “I wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for Giada. I know that for a fact. Enjoy the rest of your spring break.”

I left my seat before he could tell me he hadn’t meant what had just happened.

“You too, Miss Marshall.” He ran his hand down his face and left it over his mouth as he continued scanning the papers in front of him.

I scrambled over to my cozy booth and regained control of my senses, looking around to see if any of my classmates may have witnessed that. As much as it could have screwed things up had someone seen it, I felt like I needed some sort of confirmation that it had happened at all.

I got all the confirmation I needed when I looked up, and Gregory’s eyes met mine across the coffee shop. For the next twenty-two seconds, we were the only people in the coffee shop. Then he broke the spell, looking away, leaving me devoid of reason and racing for the door.

Gregory

It was the afternoon of the first day of classes after spring break, and technically my office hours, which I was required by the conservatory to keep, though few students ever dared to interrupt me in here. I was sipping a cup of tea, leaning back in my chair, with my feet upon the desk. Rachmaninoff was playing, not quietly. It was a new recording by the London Symphony. Such music is never meant to be played softly, as if it were background music. It demands attention. Several nagging papers from the conservatory administration lay ignored on my desk. I wasn’t prepared to deal with them, especially while wrapped in the sounds Rachmaninoff.

My eyes were closed, so I was completely unprepared for the disturbance when my office door flew open and banged into the doorframe with a loud thump. I dropped my feet to the floor, eyes darting to the door.

Marrying Ember

Marrying Ember Nocturne

Nocturne Chasing Kane

Chasing Kane Jesus Freaks: The Prodigal (Jesus Freaks #2)

Jesus Freaks: The Prodigal (Jesus Freaks #2) Something's Come Up

Something's Come Up Bo & Ember

Bo & Ember In the Stillness

In the Stillness Sweet Forty-Two

Sweet Forty-Two Jesus Freaks: Sins of the Father

Jesus Freaks: Sins of the Father The Broken Ones (Jesus Freaks #3)

The Broken Ones (Jesus Freaks #3) Bar Crawl

Bar Crawl Ten Days of Perfect (November Blue)

Ten Days of Perfect (November Blue) Reckless Abandon (November Blue, #2)

Reckless Abandon (November Blue, #2)