- Home

- Andrea Randall

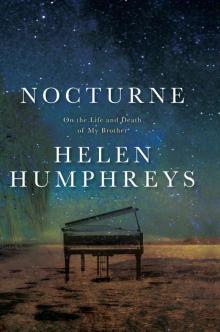

Nocturne Page 3

Nocturne Read online

Page 3

I shrugged. “Hardly. This noise is awful.”

She shook her head, a grin on her face. “You think any music written since the 18th century is awful.”

“No, that is not true. There are a number of 20th-century symphonies I absolutely love. But this?” I mock shuddered.

Karin went back to her story. And the truth was, I wasn’t terribly interested. James had insisted on setting us up for this date, sure that Karin and I would hit it off. She was attractive enough. Blonde hair, and an attractive body. But she knew little about music. How she could possibly work for the conservatory and not actually care about music? She might as well be a heathen who just happened to work in a cathedral. She went on for quite some time about the politics of the school administration, something that I cared exactly nothing about.

But I knew I was expected to say something. “That sounds ... terrible.”

She gave me a look as if she knew my words weren’t sincere. Then she gave up.

“What about you?” she asked. “When you aren’t busy with the orchestra, or teaching, what do you like to do?”

I felt my eyebrows move toward each other. “Practice. Or go to the symphony, or the occasional ballet. I’d love to see the Bolshoi someday.”

She leaned back in her chair. “Movies? Do you golf?”

I flexed my hand defensively. “Sports don’t interest me. Especially any that could injure my hands.”

She shook her head. “So really ... it’s all about the music with you?”

I gave her a long look. “It is ... all about the music.”

I studied her. It seemed I already knew an inordinate amount about her, because she’d talked quite a lot so far during dinner. She graduated with a BA in Economics from Tufts, somehow ending up at the New England Conservatory, managing, among other things, the sizeable endowment for the school. Of course I was fully aware the endowment was essential to the functioning of the school, and that financial matters must be attended to. But in truth, I’d rarely paid any attention to such things. My focus was always the music. Other things were of limited importance by comparison.

At least my student, Savannah, understood that. While her opinions were often maddening, there was no question in my mind that she got it. When she talked about music her face glowed, highlighting excited brown eyes. Although, in truth, I was concerned she might be prone to flights of fancy, and I worried far too much about her future.

Frankly, it disturbed me that I thought about her at all once class ended for the day. Never in my career had a student antagonized me as much as she did. For one crazy second, though, I wished it were her sitting across from me at the table. I wanted to hear the sweet pitch of her voice as she argued her ridiculous opinions about musical freedom, so I could argue back. That would be far more interesting than a dissertation on office politics and who on the faculty was sleeping with whom.

It was intriguing. I hadn’t intended to teach music theory at all this semester, instead concentrating on cello students exclusively. But Madeline White was injured and personally asked me to take the class. A decade ago, we’d attended the conservatory together, and had been friends ever since. She often said I was too rigid. And I, in turn, often told her she was far too freewheeling. But the respect between friends was important to me. So I took on the class. And the very first day I walked in, I didn’t miss the expression on Savannah Marshall’s face, nor that of her hyperactive boyfriend, Nathan. Both of them—the entire class, in fact—appeared horrified to see me.

I wasn’t concerned with being liked. Only respected. As long as I was teaching that course, they would get the most rigorous education possible.

Karin reached across the table and touched my hand. Her expression was a little incredulous. “Are you still there?”

I gave her a tight smile. “Please forgive me. I’m afraid I’m not quite well. It’s not your fault. Perhaps another evening?”

She looked disappointed. There was little I could do about that, and to be fair, it wasn’t her fault. I was just ... preoccupied.

Karin collected her things, and the two of us walked out of the restaurant after I paid the bill. I prided myself on being a gentleman, and this evening, I’d been no such thing, and that made me uncomfortable. I took her arm as we waited for a taxi.

“I truly am sorry. Perhaps we can meet again. I have tickets for the Boston Opera. Would you care to join me?”

Mollified, she smiled. “Yes. I’d like that very much.”

“I’m glad. I’ll call you later this week.”

She nodded as the cab rolled up. When it pulled away, I ambled down the street. I was only a few blocks from my townhouse on Pinckney Street, and I took the route that led me past a residential garden. My thoughts on a different woman than the one I’d just said goodbye to.

Gregory

A bead of sweat rolled down my forehead to my chin, where it nestled somewhere in my beard. My body was tense, my right arm beginning to tire, the left cramping. I refused to give in. It was nearly nine o’clock at night. I’d been practicing since four in the morning. The music demanded a devotion that required every bit of attention I could muster, no matter how painful it might be, no matter how much time it took. I’d devoted my life to music, letting it take priority over family, women. It took priority over everything.

I ignored the doorbell when it rang, merely frowning. There wasn’t time for interruptions. I was working on the prelude for Bach’s Suite for Solo Cello No. 3 in C Major. A beautiful piece. In fact it was the composition that had turned my interest in music from simply interest to absolute obsession. The music swept over me in waves, my eyes closed, ears turned toward the instrument, wincing every time I thought I was close to missing a beat.

The doorbell rang again, and I cursed under my breath. I couldn’t imagine who would show up at my house at nine o’clock on a Sunday evening. Whoever it was, they were infuriating.

I continued to play and ignore the doorbell. Until it rang again. And again.

Finally, I halted at the end of the movement.

Carefully, I leaned my Domenico Montagnana cello in its stand. The instrument once belonged to Pablo Casals, and I bought it at auction two years ago for seven hundred fifty thousand dollars. This, in turn, raised the ire of my entire family against me. I’d inherited the house on Pinckney Street from my maternal grandmother. Valued at just over a million dollars, a new mortgage on a property, which had been in my family for two centuries, was just enough to get my hands on an instrument without parallel; an instrument produced by one of the finest master luthiers in history, when Boston was merely a trade outpost of the British empire.

Once my instrument was in place, I walked toward the door. Immediately my legs cramped. I’d been sitting in the same position for many hours. I stood still, ignoring the now continuous doorbell. The sweat, which had rained off my body, stained the carpet for four feet around where I’d been playing, and my body was slick with perspiration.

A good practice.

I found James sagged against the doorframe as I opened it.

“It’s about time.” He rolled his eyes and scratched his head.

“You should have called ahead.”

“I did. Your phone is off, Gregory.”

I shrugged and walked back into the house, leaving the door open. James followed, his nose crinkling a little, probably at the stink of sweat I was giving off. “That’s usually a hint that I don’t wish to answer the phone.”

I walked into the kitchen and pulled a bottle of water out of the refrigerator. “Drink?” I asked.

“No, thanks.” He stood there, staring at me.

“Is something bothering you?”

James sighed. “I’m worried about you. What are you putting in right now? Eighteen hours a day? More?”

I shrugged. “I do what it takes.”

“Have you seen Karin lately?”

“We date occasionally. But she understands my music comes first and alwa

ys will.”

He shook his head slightly. “I’m sure everyone who ever comes into contact with you knows that. But you need to get out a little. There’s such a thing as having a life.”

I finished gulping back the water and tossed the bottle in the trash.

“We’ve had this discussion, James.”

“I want you to go get a shower and get dressed. Let’s go get a drink.”

I gave him a long, level look. Then I shrugged. “Fine.”

My muscles were tired, aching, and irritated with me as I climbed the stairs. James and I had been friends since both of us were students at the New England Conservatory. He was my only friend really, apart from Madeline, and certainly the only person on earth who could pull me away from practice. I’d learned to let him do it. When he decided I’d had enough, he would call and bang on the door and interrupt until I finally gave in. Generally, I found it cumbersome to have people in my life, but James’s friendship was oddly gratifying, perhaps because we’d known each other so many years. He was correct on one point. I hadn’t realized I was famished. I thought back, trying to remember when I’d last eaten, and came up with an unsatisfactory answer. It was sometime yesterday afternoon. Now that I’d stopped playing, my entire body was shaking like the vibrato I put into the strings.

Clean now, I stepped out of the shower and dried off. I changed into plain black pants, white shirt and a jacket and walked back downstairs.

“Wherever it is that we’re going, they need to have food,” I announced when I got to the bottom of the stairs.

James obliged. A few minutes later we walked into Murphy’s Pizza on the Common and sat down facing each other. A wave of exhaustion washed over me as we sat down, and James gave me a concerned look.

“Stop that,” I said. “Another lecture about how I work too hard would be tiresome.”

He shook his head and shrugged. “How long have we known each other?”

Thank God the waitress appeared at that moment. I ignored his question and looked at the menu, then placed my order. James did the same, and then he looked at me.

“Damn it, I’m not going to lecture you, but look at yourself. You’ve lost too much weight. Your clothes hang off of you. You’ve always been intense, but lately it’s seemed a little much. Even for you.”

I didn’t dignify his micro-lecture with a response. Instead I pointedly looked at the waitress, who had paused to talk to another server instead of bringing our drinks. She saw the look and started moving again, bringing us our beers.

I tasted mine. It was swill, but it would do for now.

James shook his head. “Anyway, that’s not what I came over to talk to you about. Have you thought at all about the email I sent you Thursday?”

I had received an email from James, but I couldn’t for the life of me remember what it was about.

“Refresh my memory,” I replied.

“Jesus, Gregory. It’s amazing we’ve stayed friends all these years.”

I stared across the table at him. “We have a series of shows coming up starting next week, James. I’ve had a lot on my mind.”

He frowned. “This is about the boy.”

Right. The blind boy.

“Yes, I do recall, now that you mention it. Something about a blind boy who wishes to learn cello.”

James sighed. “Don’t sound so callous. His name is Robert Donovan. From what I understand he has considerable natural talent.”

That infuriating phrase again. “Music isn’t about talent, it’s about hard work and dedication to your craft.”

“Fine, then. Whatever it is ... this kid deserves a break in life.”

“How did you encounter him?”

“I met his adoptive parents a few weeks ago at a dinner party.”

“Adoptive?”

James nodded. “Robby was severely abused when he was younger. His birth parents are in prison. They actually thought he was autistic, but that … seems to be trauma. He’s brilliant.”

“And what exactly does this have to do with me? Surely you can find some...” I waved my hand in the air, trying to find a phrase that wouldn’t sound as arrogant as I knew this was going to sound. After flailing uselessly for a moment, I said what I had on my mind. “Surely you can find some second-rate cello instructor to help this boy with his playing.”

Our meals arrived as we spoke, so we paused for a few moments. Once the waitress was gone, James spoke. “This kid has a remarkable ear, Gregory. We’re talking a couple of hours a week.”

“I don’t do private lessons outside of the conservatory. You know that.”

“I want you to consider an exception. Just meet him over spring break and listen to him play.”

I sighed and very slightly shook my head, then took a sip of the “beer”. “Fine, James. I’ll meet him. I’ll consider it. I’m not promising anything. It’s one thing teaching students at the conservatory ... but it’s another thing to teach someone entirely new to music.”

Especially someone who’s blind.

I had no idea how I’d stand a chance teaching a young child how to play notes he couldn’t read on a page, or see the location of my fingers on the strings. I’d figure something out.

James grinned. “Tuesday? 4 p.m.?”

“Certainly. Whatever you require. Just tell me where to be and leave me alone about it.”

James’s voice trailed off in my head as the bells on the door directed my eyes upward, where I saw Savannah Marshall and a group of her girlfriends. I was slightly annoyed, at first, that the waitress sat them at the booth diagonal from ours, given all their high-pitched giggling and incessant talking. The irritation lasted only as long as it took for Savannah to remove her oversized white winter jacket, revealing a snug red sweater underneath it.

Any time I’d seen her in class or on stage, she mostly dressed professionally. Apart from her wildly inappropriate audition clothing three years ago, of course. That aside, I respected that she never seemed to put herself on display the way so many of her female classmates did. This sweater, however, clung to the severe curve of her waist in a way that made my lips part and take in an extra breath.

She was stunning. Absolutely stunning.

Prying myself away from staring inappropriately, I peered up to her face. Just as she turned to sit, Savannah caught my eye, seemingly startled to see me. Her already wind-blushed cheeks deepened in color as she took a visible breath.

“Hi Mr. Fitzgerald,” she said melodically as she politely waved.

Gregory, please. Call me Gregory.

I didn’t say that. I did, however, return her greeting with a grin and a wave of my own. “Savannah,” I replied, nodding once.

“Wh—were you even listening to me?” James held out his hands, exasperated.

“Calm down, James. A student said hi. I was trying to have a life, as you suggested earlier.”

James turned to the gaggle of laughing girls and shook his head, looking back at me.

“What?” I asked as his face turned suspicious.

He shook his head, grinning as he took a sip of his beer. “Nothing. Just watch your ass, Greg.”

Rolling my eyes, I sipped my beer, too. “Must you be so crass, James?”

“Yes,” he chuckled, mocking me, “I must.”

Savannah

Assobio a Jato.

My senior recital wasn’t for over a year, but I knew I’d be playing this piece as part of my program the second I heard it. It’s a piece for flute and cello, and I planned on asking my friend and roommate, Marcia, to accompany me. I was lucky Gregory Fitzgerald hadn’t overheard me practicing this piece when he saw me the other day in the practice rooms. I’m sure he would have given me an earful about how I was “doing it wrong,” since he didn’t seem to like me very much. At first I assumed his gruffness toward me was because of my mother, but he didn’t seem to have an idea of who she was. Well, he probably knew who she was, but not that she was my mother. I chuckled a little,

recalling that I’d put my mother’s married name any place on the application that asked for my parents’ names. I’d wanted to get in on my own.

Each year there was always a fresh batch of rumors about who got in and why. Some people were accused of bribing members of the pre-audition committee in various ways, but others, reportedly, took it all the way to the top and went for the jugular. Paying off the school.

I knew there were enough people at the conservatory that knew who my mother was, but the fact that Gregory Fitzgerald didn’t calmed me somehow.

Marcia rolled her eyes when I told her Fitzgerald was the new instructor for my music theory class. Luckily, Madeline was able to set me up with a trusted colleague of hers to provide my private instruction for the remainder of the semester. Marcia actually had Gregory, as he requested she call him—which shocked the hell out of me for some reason—for her private instruction. She was thrilled to learn from the best cellist at the conservatory, and, really, in the country, but she found his style a bit militant.

I shook my head, lifted my chin, and resumed practicing.

Open throat. Don’t let your fingers get ahead of your eyes.

I don’t know why the hell Gregory Fitzgerald got under my skin.

Yes, I do. He was an arrogant, snobby musical stereotype of the worst kind. He barely looked out into the class when he was talking, and when he did, his clear blue eyes shot through me like ice. He was only ten years or so older than me. His thick, black hair and fairly tight physique spoke to that. But the grim, smug expression he plastered on his face aged him another ten. Easily.

Seeing him at Murphy’s with James Mahone that day caught me off guard. I wanted to blow him off, ignore him the way he ignores all of us when we’re out in public. But, he wasn’t ignoring me. I’d caught him staring at me, and it didn’t infuriate me. It excited me. I felt his eyes on me as I took off my coat, and when I turned toward him, those blue eyes pulled a juvenile hi from me before I could filter it. He grinned back, returned the greeting, and I wanted to melt. He might be human after all, I thought.

Marrying Ember

Marrying Ember Nocturne

Nocturne Chasing Kane

Chasing Kane Jesus Freaks: The Prodigal (Jesus Freaks #2)

Jesus Freaks: The Prodigal (Jesus Freaks #2) Something's Come Up

Something's Come Up Bo & Ember

Bo & Ember In the Stillness

In the Stillness Sweet Forty-Two

Sweet Forty-Two Jesus Freaks: Sins of the Father

Jesus Freaks: Sins of the Father The Broken Ones (Jesus Freaks #3)

The Broken Ones (Jesus Freaks #3) Bar Crawl

Bar Crawl Ten Days of Perfect (November Blue)

Ten Days of Perfect (November Blue) Reckless Abandon (November Blue, #2)

Reckless Abandon (November Blue, #2)